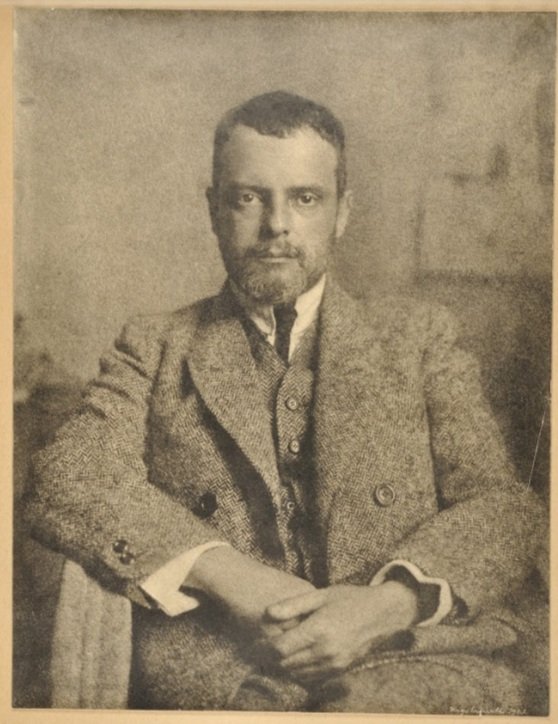

Paul Klee

Swiss

b. December 18, 1879, Munchenbuchsee, Switzerland —

d. June 29, 1940, Locarno, Switzerland

Childhood

Paul Klee was born to a German father who taught music at the Berne-Hofwil teacher's college and a Swiss mother trained as a professional singer. Encouraged by his musical parents, he took up violin at age seven. His other hobbies, drawing and writing poems, were not fostered in the same way. Despite his parents' wishes that he pursue a musical career, Klee decided he would have more success in the visual arts, a field in which he could create rather than just perform.

Early Training

Klee's academic training focused mostly on his drawing skills. He studied in a private studio for two years before joining the studio of German symbolist Franz von Stuck in 1900. During his studies in Munich, he met Lily Stumpf, a pianist, and the couple married in 1906. Lily's work as a piano instructor supported Klee's early years as an artist, even after the birth of their son, Felix, in 1907.

Klee remained isolated from the developments of modern art until 1911, when he met Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, and August Macke of Der Blaue Reiter. He participated in the second Blaue Reiter exhibition in 1912 and saw there the work of other avant-garde artists such as Robert Delaunay, Pablo Picasso, and Georges Braque. Klee visited Delaunay's studio in Paris that same year. His experiments with abstraction began at about this time.

Klee's trip to Tunisia in 1914 changed his relationship with color. "Color and I are one," he declared in his diaries. "I am a painter." Traveling with August Macke and Louis Moilliet, he drew and painted watercolor landscapes of Tunis, Hammamet, and Kairouan. After Klee's return, he created several abstract works based on his Tunisian watercolors.

Mature Period

Klee's views on abstract art were influenced by Wilhelm Worringer's thesis Abstraction and Empathy (1907), which hypothesized that abstract art was created in a time of war. World War I broke out only three months after Klee had returned from Tunisia. Klee was called to duty in 1916, but was spared the front. Meanwhile, he enjoyed financial success, especially after a large exhibition in Der Sturm Gallery in Berlin. Klee was reserved in his opinions against the war, but when a communist government was declared in Munich in November 1918, he enthusiastically accepted a position on the Executive Committee of Revolutionary Artists. The November Revolution failed soon thereafter and Klee returned to Switzerland.

Klee accepted an invitation to teach at the Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar in 1920. The Bauhaus was an influential school of architecture and industrial design that aimed to provide students with a grounding in all of the visual arts. Klee taught at the school for ten years, moving with the Bauhaus from Weimar to Dessau in 1925. He taught workshops in book binding and painting stained glass, but his influence as a teacher was most noted in his series of detailed lectures on visual form (Bildnerische Formlehre).

In 1930 Klee left the Bauhaus for the art academy in Düsseldorf, but this brief period of calm ended on January 30, 1933, when Hitler was named Chancellor of Germany. Klee was denounced as a "Galician Jew" and a "cultural Bolshevik," and his work derided as "subversive" and "insane." His house in Dessau was searched, and in April 1933 he was dismissed from his teaching position. Klee and his wife returned to Berne in December.

Late Period and Death

Two years after returning to Switzerland, Klee fell ill with a disease that would later be diagnosed as progressive scleroderma, an autoimmune disease that hardens the skin and other organs. The artist created only 25 works the year after he fell ill, but his creativity resurged in 1937 and increased to a record 1,253 works in 1939. His late works dealt with the grief, pain, resilience, and acceptance of approaching death.

Several of Klee's works were included in the "Degenerate Art" exhibition staged by the National Socialists in Munich in 1937. The accusations against Klee's character and politics that had been waged against him in Germany complicated his application for Swiss citizenship in 1939. While he had been born in Switzerland, his father was German, which according to Swiss law meant that Klee was a German citizen. Klee died on June 29, 1940 in Locarno, Switzerland, before his final application could be approved.

The Legacy of Paul Klee

Klee's artistic legacy has been immense, even if many of his successors have not referenced his work openly as an apparent source or influence. During his lifetime, the Surrealists found Klee's seemingly random juxtaposition of text, abstract signs, and reductive symbols suggestive of the way the mind in dream state recombines disparate objects of everyday and thus brings forth new insights into how the unconscious wields power even over waking reality.

In European art after the 1940s, artists such as Jean Dubuffet continued to reference the art of children as a kind of untutored, expressive ideal. Klee's reputation grew considerably in the 1950s, by which time, for instance, the Abstract Expressionists could view his work in New York exhibitions. Klee's use of signs and symbols particularly interested the artists of the New York School, especially those interested in mythology, the unconscious, and primitivism (as well as the art of the self-trained and that of children). Klee's use of color as an expressive medium of human emotion in its own right also appealed to the Color Field painters, such as Jules Olitski and Helen Frankenthaler. Finally, American artists maturing in the 1960s and 1970s, such as Ellsworth Kelly owed a debt to Klee for his pioneering color theory during the Bauhaus period.

Senecio, 1972

Lithograph

26 x 20 inches

Ed. 261/375

Unframed